Despre intervievat, cu Mike Sager

Textul de mai jos a fost scris de către Simina Mistreanu, editor asociat la Decât o Revistă și un om minunat, pentru cursul Interview Essentials din semestrul de primavara 2012, predat de Jacqui Banaszynski, la Missouri School of Journalism, unde Simina e studentă.

Tema era sa vorbesti cu un intervievator profesionist despre tehnicile si filosofia pe care le respecta atunci cand intervieveaza. Simina l-a intervievat pe Mike Sager, contributing writer la Esquire US și unul dintre invitații ediției din 2012 a The Power of Storytelling. Au vorbit pe Skype, timp de aproximativ o oră. Textul l-am păstrat în engleză de dragul acurateței conversației.

Mike va povesti și mai multe la conferință despre ce numește mai jos “suspension of disbelief” și despre tehnicile de documentare pe care le folosește.

—–

I had a Skype interview with Mike Sager on Saturday, March 3. At the beginning of the conversation, he showed me his interviewing equipment. He uses an Olympus voice recorder and a few accessories: an earphone for phone conversations, a lavaliere microphone and a foot pedal for transcribing interviews.

Below are some of the things I learned from Sager, in his own words:

On transcribing:

Honestly, transcribing every single bit of tape has been one of the secrets of my success.

It often will take a couple of weeks to transcribe a story. Even to the point when now I”™m kind of old, and I have tendonitis, and I have help transcribing. So they do it, but I still listen to it all and read it and fix it wherever they missed. That process is usually about a third of my time spent on the entire story. I”™d say reporting is a third, and then transcribing is always a third, and then writing is a third. Usually, the writing is a little more rushed, so it”™s probably less than that. And that”™s really my favorite part.

On building rapport:

People say that my stories, it”™s almost like I do different accents. What I often do is I quote people without using quotes. I just use their words. That way I get all the terminology, and I can fluid in the person, and I can steep like a tea bag in the thing.

I evolved the technique of being like a reality-show camera. A lot of reporters are so hype; they go running in with all their questions prepared. I go in, and I don”™t ask anything. I”™m just really nice. And if something drops, I pick it up, and I buy lunch. I try to be friendly. I”™m just really interested. You know, mothers teach their daughters what to do on dates. I”™m just like the greatest date ever. Boy, girl, whatever you are, I”™m your great date.

And also, I”™m very observant. That”™s what I do, I just observe. It”™s like I”™m watching TV in 3D.

I know there”™s an incident that I need to know about. And then you know the general outline of the story, but what I just do is start in chronological order. And then, literally, I”™ve said to almost every single person I”™ve ever interviewed, “œSo you were born in a log cabin.”

It”™s sort of like foreplay. You don”™t jump right in, you got to warm him up. You have foreplay, you ask about their lives. It”™s easy for people to tell you that. That”™s what I do; I go through and I lead up to “œAnd so, then you shot him. Tell me about that day when you first got together with the guy.” Whatever, you know where you have to go, but just start at the beginning and ask the easy stuff.

You save your hardest questions till the end. I always do that with everybody.

On suspending disbelief:

I have this thing I call “œsuspension of disbelief.” At the time I met the Aryan Nations people who were hate mongers, who were against black people and Jews and all that kind of stuff, I”™m Jewish, and I was married to a black woman, and I had a kid who was half-and-half. I”™m going in there, and they”™re like “œAre you a Jew?” I”™m like “œNo, I”™m Italian.”

[But] the guy”™s wife is dying in the back cottage and I try to understand.

When you”™re doing these stories that are so deep and personal, the rules are even more stringent than any rules of man. These are the rules of God and the heart. If I follow those rules, then I never fuck up.

I”™ve been reporting this story for a year; I finally get the jailhouse interview with the killer. So what? I know he”™s going to have a horrible life; he”™s going to be in jail. And the Thai Buddhists that he killed, they believe he”™s going to have a thousand lifetimes of damnation. So why do I have to judge him, right? I”™m there to find out what it”™s like to be him. And he”™s like “œAnd then we shot him.” And I”™m like the same thing I say to my 10-year-old, my 18-year-old, whatever age: “œCool! What was that like?” And he told me: it made a gushing, bubbling sound, and he described what it”™s like to shoot someone in the head. We love these stories about death and dying. We just want one more detail. We want to know one step further. We know he killed them, but then we don”™t know anything else. What is it like?

On Mike Sager, the interviewer:

I”™m afraid to be lost, I don”™t like to go anywhere, I don”™t want to talk to anybody. But once I”™m there I have my fucking cape on, I”™m Superman. All these questions, all these emotions, all this strong shit. As a journalist, it gets in the way. Use the passion for the writing. But you”™re not going to be the same person if you shut the fuck up and listen for a minute and learn.

I think people are afraid to be wrong. As a journalist, that”™s my biggest strength ““ I”™m great at being an idiot. I don”™t have to be smart. I know what it takes to be able to listen. And like listen in a way that you”™re like, “œHoly shit, I never even thought of it that way.”

Often, what people need is just approval and an ear. And that I”™m really good at doing, and nodding my head and suspending my disbelief. Now, if they were a heinous criminal, at the end I have to ask that question, too. But I ask a “œHow does it feel to be you” kind of question instead of “œSociety”¦” I ask the real question.

I believe that Hitler”™s girlfriend, Eva Braun, probably liked something about him. It was something lovable about Hitler. If you want to write a really good Hitler character, then if he has a little goodness in him, then you feel bad that he”™s such an asshole instead of just wanting to kill the asshole. And that is drama.

I don”™t like [interviewing] at all. And every once in a while, I meet a really great person. I learned a lot from the real people. I end up liking that. It”™s very inconvenient and uncomfortable. It”™s like being in the greatest ride in the world when you”™re like suddenly in the middle of something.

Over the years, what this job has done more than anything is molded me into being a certain kind of person. I am the sum total of all the people I”™ve met. All the weird, fucking things that people have said to me and all the stuff that I”™ve done and the places I”™ve been, I am that person, I am not who I was when I began.

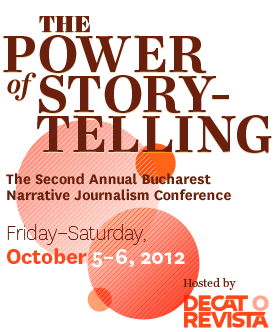

The Power of Storytelling 2012

Pe 5-6 octombrie, Decât o Revistă și asociația Media DoR organizează la Pullman/World Trade Center în București a doua ediție a conferinței de jurnalism narativ pe care am început-o anul trecut. În 2011 au fost 200 de participanți și am avut patru invitați excepționali, care au vorbit despre ce te face un povestitor mai bun și, mai ales, cum construiești o poveste mai puternică, mai emoționantă și mai convingătoare.

Am fost și mai curajoși anul ăsta când am început să invităm speakeri – din SUA, pentru că acolo se face genul acesta de jurnalism cel mai bine. Deja se știe în unele cercuri că există un buzunar de jurnalism narativ în România, așa că munca de a convinge invitații nu a fost prea grea.

Totuși, cei nouă invitați pe care îi vom avea anul acesta întrec și cele mai curajoase vise de-ale mele. Pe Mike Sager și pe Chris Jones îi citesc de prin 2004 și sunt unii dintre cei responsabili pentru ce-mi doresc să scriu și să editez. Articolul lui Mike Sager despre cum a călătorit prin America ca să cunoască alți Mike Sager l-am predat la cursuri și e o dovadă a cum vocea și experiența de reporter pot transforma un subiect banal într-o meditație despre sensul vieții. Textul lui Chris Jones, The Things That Carried Him, m-a marcat atât de mult la prima citire încât primul meu impuls a fost să-i scriu și să-i spun că ce a produs este un monument de documentare și scriitură și că aș da orice să știu cum a construit materialul. (Mi-a răspuns).

Despre Jacqui Banaszynski și cât îi sunt de dator, am mai scris. Nu mă voi sătura niciodată să o aud vorbind despre structură și nu voi uita niciodată incantația ei despre povești, care se termină așa: Stories are our soul; so write and edit and tell yours with your whole selves. Tell them as if they are all that matters.

Pat Walters vine de la Radiolab, iar Starlee Kine vine de la This American Life, care, chiar dacă sunt emisiuni de radio, sunt exemple copleșitoare de cum poți folosi poveștile să explici orice — de la corupție în justiție, la găuri negre, la ce înseamnă monogamia.

Alex Tizon a fost aici și anul trecut și i-a plăcut atât de tare încât s-a oferit să mai vină odată. Pentru că și publicul l-a iubit, n-am putut decât să mă bucur.

Când am văzut pentru prima oară un reportaj video de Travis Fox, le-am scris celor de la Washington Post că are ceva cu România. Acum știu că nu avea și mai știu că reacția pe care mi-a produs-o avea legătură cu capacitatea lui de a filma și monta imagini în așa fel încât să nu te lase rece. Astăzi cred că bucata lui din 2006Â e la fel de relevantă pentru România de azi cum era și atunci.

Evan Ratliff m-a demolat cu Vanish, textul lui din Wired despre cum a încercat să dispară într-o lume dominată de instrumente electronice care ne urmăresc fiecare mișcare. Iar când a făcut The Atavist, l-am invidiat sincer pentru curajul de a intra din scris în antreprenoriat.

Ultimul, dar nu cel din urmă, e Walt Harrington. L-am văzut în 2004 la o conferință de jurnalism narativ în St. Louis, într-o vreme în care nu prea înțelegeam ce e cu forma asta. Prelegerea lui de atunci, despre diferențele dintre realitate și ficțiune în scris și motivul pentru care un jurnalist nu are voie se pună nimic de la el, mă urmăresc și azi. (Walt va livra o versiune a pledoariei lui pentru adevăr și la București).

Tot de la el am împrumutat sintagma news you can feel, care descrie minunat acest fel de muncă. Și mai sunt.

E un vis împlinit că îi putem aduce pe toți acești oameni senzaționali la București și sunt convins că ne vor bombarda cu inspirație și ne vor face povestitori mai buni, indiferent că lucrăm în jurnalism, comunicare sau vrem doar să găsim cele mai multe unelte ca să împărtășim ceva din experiența umană cu cei din jur, colegi sau familie. Cu siguranță unii dintre noi vor avea șansa să răspundă la întrebări importante despre motivele pentru care vor să povestească altora despre lumea în care trăim. Închei cu ce spune Walt Harrinton pe această temă:

I have a wife, children, friends who touch me daily. They are the best piece of my life. But, as is true for so many others, it’s not enough. Doing journalism has become my personal answer to the hollowness, the human disconnect, of modern life. I’m not saying it’s healthy or normal or good that I feel this way about my stories. I’m not saying it’s a legitimate journalistic motivation.

I’m saying only that it’s true. The words satisfaction or accomplishment don’t describe the sensations I get reporting and writing stories ““ awe or amazement or communion hit closer to home.

PS: Vă puteți înregistra la conferință aici.